[Luke, Typed Letter Signed (TLS) on Lambeth Palace stationery from Bishop George

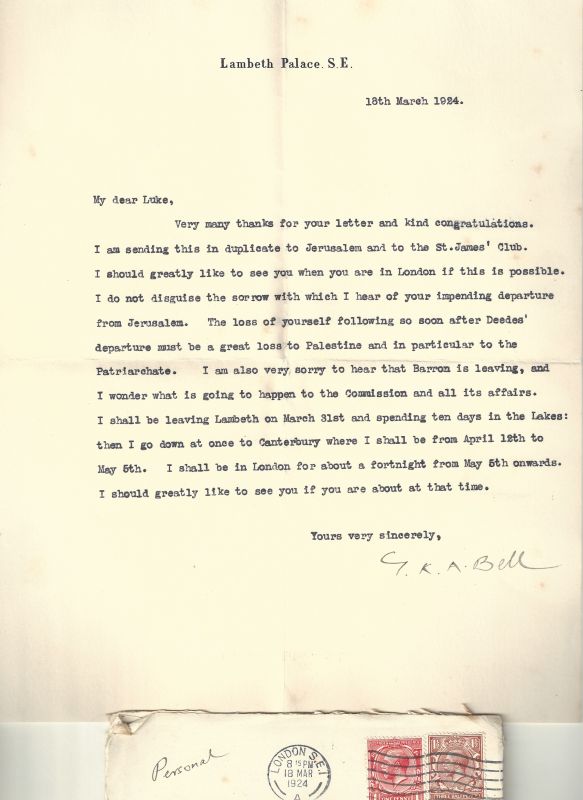

Typed Letter Signed (TLS) on Lambeth Palace stationery from Bishop George Kennedy Allen Bell to Sir Harry Luke: ‘My dear Luke – very many thanks for your letter and kind congratulations. I am sending this in duplicate to Jerusalem and to the St. James’ Club. I should greatly like to see you when you are in London if this is possible. I do not disguise the sorrow with which I hear of your impending departure from Jerusalem. The loss of yourself following so soon after Deedes’ [Brigadier General Sir Wyndham Henry Deedes] departure must be a great loss to Palestine and in particular to the Patriarchate. I am also very sorry to hear that Barron [J.B.Barron of the Palestine Land Commision Weights and Measure Commission] is leaving and I wonder what is going to happen to the Commission and all its affairs. I shall be leaving Lambeth on March 31st and spending ten days in the Lakes: then I go down at once to Canterbury where I shall be from April 12th to May 5th. I shall be in London for about a fortnight from May 5th onwards. I would greatly like to see you if you are about at that time. Yours very sincerely, G.K.A. Bell.

[This item is part of the Sir Harry Luke – Archive / Collection]. Lambeth Palace, 18th March 1924. Octavo. 1 page with original envelope. From the private collection / library of colonial governor, diplomat and historian, Sir Harry Luke.

George Kennedy Allen Bell (4 February 1883 – 3 October 1958) was an Anglican theologian, Dean of Canterbury, Bishop of Chichester, member of the House of Lords and a pioneer of the ecumenical movement.

Born in Hayling Island, Hampshire, as the eldest child of Sarah Georgina Megaw and her husband James Allen Bell (the vicar of the Island and later a canon at Norwich Cathedral), Bell was elected as a Queen’s Scholar at Westminster School in 1896. From there he was elected to a scholarship at Christ Church, Oxford, where he gained a First in Classical Moderations in 1903 and a Second in Literae Humaniores (‘Greats’) in 1905.[1] He won the Newdigate Prize for English verse in 1904 for his poem, ‘Delphi’.[2] After Oxford he attended Wells Theological College (first being influenced by ecumenism at the latter) and was ordained deacon at Ripon Cathedral in 1907. He went on to work as a curate for three years in the industrial slums of Leeds. His role there was the Christian mission to industrial workers, a third of whom were Indians and Africans from the British Empire.[citation needed] During his time there he learned much from the Methodists, whose connection between personal creed and social engagement he saw as an example to the Church of England.

In 1910 Bell returned to Christ Church, Oxford, as a student minister and as lecturer in Classics and English, 1910–14; he was a Student (Fellow), 1911-14. Here too he was socially engaged, as one of the founders of a cooperative for students and university members and sitting on the board of settlements and worker-development through the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA).

Bell’s early career was shaped by his appointment in 1914 as chaplain to Archbishop Randall Davidson, one of the key figures in twentieth century church history. Bell subsequently wrote the standard biography of Davidson. Bell received a special commission for international and inter-denominational relations. In this office he ensured in 1915 that the Lutheran Indians be allowed to continue the work of the Leipzig – and the Goßner missions in Chota Nagpur in India, after the missions’ German missionaries had been interned. Until the end of the First World War, he also worked for the Order of Saint John, a supra-confessional group working to help those orphaned by the war and – together with the Swedish Lutheran archbishop Nathan Söderblom, one of his closest lifelong friends – for the exchange of prisoners of war. In this work, he came to see internal Protestant divisions as more and more insignificant.

After the war, Bell became an initiator and promoter of the still-young ecumenical movement. In 1919, at the first postwar meeting of the World Council of Churches in the Netherlands, he successfully encouraged the establishment of a commission for religious and national minorities. At the world churches conference in Stockholm in 1925, he helped in the realisation of the “ecumenical advice for practical Christianity (Life and Work)”. From 1925 to 1929, Bell was Dean of Canterbury. During this time, he initiated the Canterbury Festival of the arts, with guest artists such as John Masefield, Gustav Holst, Dorothy L. Sayers and T. S. Eliot (whose 1935 drama Murder in the Cathedral was commissioned by Bell for the festival). Later Bell also received Mahatma Gandhi at Canterbury.

In 1929 Bell was appointed Bishop of Chichester. In this role he organised links between his diocese and of workers affected by the Great Depression. He also took part in the meetings of the National Union of Public Employees, where he was welcomed as “brother Bell”.

From 1932 to 1934 he was the president of “Life and Work” at the ecumenical council in Geneva, at whose Berlin conference at the start of February 1933 he witnessed the Nazi takeover at first hand.

After 1933, Bell became the most important international ally of the Confessing Church in Germany. In April 1933 he publicly expressed the international church’s worries over the beginnings of the Nazis’ antisemitic campaign in Germany, and in September that year carried a resolution protesting against the “Aryan paragraph” and its acceptance by parts of the German Evangelical Church (Deutsche Evangelische Kirche, or DEK). In November 1933 he first met Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was in London for two years as representative of the foreign churches – the two became close friends, and Bonhoeffer often informed Bell of what was going on in Germany. Bell then made this information (and thus what was really happening in Germany) known to the public of Europe and America, for example through letters to The Times.

On 1 June 1934 he signed the Barmen Declaration, the foundational manifesto of the Confessing Church – it proclaimed that Christian belief and National Socialism were incompatible, and condemned pro-Nazi German Christianity as “false teaching”, or heresy. Bell reported on 6 June to a gathering of the bishops of the Church of England and clarified the difference between confessing and rejecting, and the separation between a lawful and an illegitimate calling on Jesus Christ. This was the first reaction to the Declaration from the international church.

From 1934 Bell functioned as a president of “Life and Work”, when Bonhoeffer and Karl Koch as praeses of the synod of the old-Prussian Ecclesiastical province of Westphalia were invited as representatives of the Confessing Church to the world ecumenical conference in Fanø. As a selected youth secretary, Bonhoeffer was responsible for the related world youth conference. At one morning service, he addressed world Christianity as an “ecumenical council” and called on it to rise against the threatened war. On Bell’s suggestion and against protests from the representatives of the pro-Nazi DEK, the world conference expressed solidarity with the Confessing Church and its struggle and again exposed the Nazis’ policies, including the concentration camps.

In 1936 Bell received the chair of the International Christian Committee for German Refugees, and in that role he especially supported Jewish Christians, who at that time were supported by neither Jewish nor Christian organizations. In order to help them to emigrate, he dispatched his sister-in-law Laura Livingstone to Berlin and Hamburg and occasionally let exiles live in his own home. In the same year, he printed a prayer in his diocesan newsletter for Jewish and “non-Aryan” Christians:

“ Pray for the Jews in Stepney, and Whitechapel, and Bethnal Green [where exiles were often accommodated]; pray for the German Jews; for all who suffer pain, who suffer shame, on account of their race. Pray for those who have a Jewish parent or grandparent and are Christian by belief… ”

Bell used his authority as a leader in the Ecumenical Movement and since 1938 as Lord Spiritual to influence public opinion in Britain and the Nazi authorities in Berlin, and back those persecuted by the Nazi regime. His public support is said to have contributed to Pastor Martin Niemöller’s survival by making his imprisonment in Sachsenhausen in February 1938 (and later in Dachau) widely known in the British press and branded as an example of the Nazi regime’s persecution of the church. Thus Hitler backed off from Niemöller’s planned execution in 1938.

In winter 1938/39 he helped 90 persons, mainly pastors’ families (e.g. Hans Ehrenberg from the Christuskirche at Bochum), to emigrate from Germany to Great Britain who were in danger from the regime and the ‘official’ church because they had Jewish ancestors or were opponents of the Nazi regime.

During the war, Bell was involved in helping not only displaced persons and refugees who had fled the continent to England, but also interned Germans and British conscientious objectors. In 1940 he met with ecumenical friends in the Netherlands to unite the churches ready for a joint peace initiative after victory over Nazi Germany had been won.

During World War II Bell repeatedly condemned the Allied practice of area bombing. As a member of the House of Lords, he was a consistent parliamentary critic of area bombing along with Richard Stokes and Alfred Salter, Labour Party Members of Parliament in the House of Commons.

Even as early as 1939, he stated that the church should not be allowed to become simply a spiritual help to the state, but instead should be an advocate of peaceful international relations and make a stand against expulsion, enslavement and the destruction of morality. It should not be allowed to abandon these principles, ever ready to criticise retaliatory attacks or the bombing of civil populations. He also urged the European churches to remain critical of their own countries’ ways of waging war. In November 1939 he published an article stating that the Church in wartime should not hesitate

“to condemn the infliction of reprisals, or the bombing of civilian populations, by the military forces of its own nation. It should set itself against the propaganda of lies and hatred. It should be ready to encourage the resumption of friendly relations with the enemy nation. It should set its face against any war of extermination or enslavement, and any measures directly aimed to destroy the morale of a population.”

In 1941 in a letter to The Times, he called the bombing of unarmed women and children “barbarian” which would destroy the just cause for the war, thus openly criticising the Prime Minister’s advocacy of such a bombing strategy. On 14 February 1943 – two years ahead of the Dresden raids – he urged the House of Lords to resist the War Cabinet’s decision for area bombing, stating that it called into question all the humane and democratic values for which Britain had gone to war. In 1944, during debate, he again demanded the House of Lords to stop British area bombing of German cities such as Hamburg and Berlin as a disproportionate and illegal “policy of annihilation” and a crime against humanity, asking:

“How can the War Cabinet fail to see that this progressive devastation of cities is threatening the roots of civilization?”

He did not have the support of senior bishops. The Archbishop of York replied to him in Parliament “it is a lesser evil to bomb the war-loving Germans than to sacrifice the lives of our fellow countrymen…, or to delay the delivery of many now held in slavery”.

As a close friend of the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer Bell knew precise details of German plans to assassinate Adolf Hitler. On 1 June 1942, Bell met Bonhoeffer in neutral Sweden, where the latter was acting as a secret courier for information on the German resistance. This information included the names of the participants from the armed forces in the planned assassination attempt on Hitler and coup against the Nazi regime.

On his return, Bell passed this information on the German resistance movement on to Anthony Eden and tried to gain British government support for them. Bell also asked Eden, at the conspirators’ request “to emphatically and publicly explain that the British government and its allies have no wish to enslave Germany, but only to remove Hitler, Himmler and their accessories” – in other words, to make a public declaration that the British would make a distinction between the Nazi regime and German people, so as the conspirators would be able to negotiate an armistice if they were successful. Yet after a month-long silence, Bell received a rough rebuttal, for the allies had concluded at the Casablanca conference to wage war until the unconditional surrender of Germany and to initiate area bombing. Such moves made Bell unpopular in some quarters. Noël Coward’s 1943 song “Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Germans”, which expressed hostility to any distinction between the Germans and the Nazis, commented “We might send [the Germans] out some Bishops as a form of lease and lend”.

After the failure of the first attempt on Hitler’s life and the arrest of some of the conspirators, Bell in vain tried to bring about a change in government attitudes to the German resistance. When the final failure came on 20 July 1944, Bell harshly criticised the British government as having made this failure a foregone conclusion, and reproached Eden for not sending help to the plotters in time despite having full knowledge of the plot.In 1944 the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple, died after only two years in the post. Bell was considered a leading possibility to succeed him, but it was Geoffrey Fisher, Bishop of London, who was appointed. Bishops of the Church of England are chosen, ultimately, by the British prime minister and it is known that Winston Churchill strongly disapproved of Bell’s speeches against bombing. It has often been asserted that Bell would otherwise have been appointed, but this is debatable; there is evidence that Temple had thought Fisher a likely successor anyway. Bell’s high posthumous reputation may have coloured later opinion (for example, Archbishop Rowan Williams said in 2008 that he thought Bell would have made a better Archbishop of Canterbury than Fisher). Bell was also one of the first British bishops to protest against the inhumane treatment of approximately 14 million Silesian, Pomeranian, East Prussian and Sudeten Germans expelled from their homes in Eastern Europe. Around 15 August 1945, he signed an open letter of protest in The Spectator, and signed another protest to a London daily newspaper on 12 September that year alongside the British Jewish publisher Victor Gollancz, Bertrand Russell and others.

In the 1950s Bell opposed the atomic arms race and supported many Christian initiatives of the time opposed to the Cold War. In the last years of his life, he became acquainted with Giovanni Montini in Milan through his ecumenical contacts, who in 1963 became Pope Paul VI and brought the Second Vatican Council to its conclusion. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: Bell, Bishop George Kennedy Allen · British Colonial Administration · British Colonial History · British Foreign Office · British Foreign Policy · Colonial administrators · Colonial History · Colonial History – Rare · Deedes, Sir Wyndham Henry · Ecclesiastical · Ecclesiastical Content / Sir Harry Luke · Harry Luke – Ecclesiastical · Jerusalem · Lambeth Palace Canterbury · Middle Eastern History · Middle Eastern History – Rare · Palestine · Sir Harry Luke · Sir Harry Luke – Personal Archive of Books and Correspondence · Sir Harry Luke Collection

- Language: English

- Inventory Number: 30247AB

EUR 275.000,--

© 2024 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software