O'Casey, Three Volumes of Sean O'Casey's famous Autobiography: I. I Knock at the

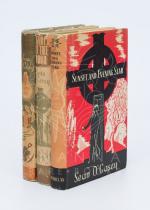

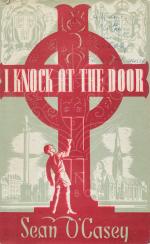

Three Volumes of Sean O’Casey’s famous Autobiography: I. I Knock at the Door – Swift Glances Back at Things That Made Me (Rare Second Edition, Printed in the year of the First Edition, 1939) / III. Drums under the Windows (First Edition 1945) / VI. Sunset and Evening Star (First Edition, 1954).

Three Volumes (of Six). London, MacMillan & Co., 1939 – 1954. Octavo (15 cm x 22 cm). Volume I (″I Knock at the Door”): includes a fine Frontispiece-Photograph of “Mrs.Susan Casside in a Gala Dress”, VII, 268, [3] pages / Volume III (″Drums under My Window”): includes a Frontispiece-Photograph of “The Rev.E.M.Griffin”, 339, [2] pages / Volume VI (″Sunset and Evening Star”: includes a very fine Frontispiece-Photograph of “The O’Casey’s” [Niall O’Casey, Breon O’Casey, Sean O’Casey, Shivawn [Shivaun] O’Casey, Eileen O’Casey], VII, 311, [1] pages. Original Hardcover with illustrated dustjackets. All three Volumes in their original state with the original dustjackets frayed but still very good. Volume I and III with two excellent Bookplates / Giftnote to dustjacket of Volume I; Giftnote to endpaper of Volume VI. Exlibris to pastedown “The Vernons” with artwork from artist H. Cutler” .

Seán O’Casey (born John Casey; 30 March 1880 – 18 September 1964) was an Irish dramatist and memoirist. A committed socialist, he was the first Irish playwright of note to write about the Dublin working classes.

O’Casey was born at 85 Upper Dorset Street, Dublin, as John Casey, the son of Michael Casey, a mercantile clerk (who worked for the Irish Church Missions), and Susan Archer. His parents were Protestants and he was a member of the Church of Ireland, baptised on 28 July 1880 in St. Mary’s parish, confirmed at St John the Baptist Church in Clontarf, and an active member of St. Barnabas’ Church on Sheriff Street until his mid-20s, when he drifted away from the church. There is a church called ‘Saint Burnupus’ in his play Red Roses For Me.

O’Casey’s father died when Seán was just six years of age, leaving a family of thirteen. The family lived a peripatetic life thereafter, moving from house to house around north Dublin. As a child, he suffered from poor eyesight, which interfered somewhat with his early education, but O’Casey taught himself to read and write by the age of thirteen.

He left school at fourteen and worked at a variety of jobs, including a nine-year period as a railwayman on the GNR. O’Casey worked in Eason’s for a short while, in the newspaper distribution business, but was sacked for not taking off his cap when collecting his wage packet.

From the early 1890s, O’Casey and his elder brother, Archie, put on performances of plays by Dion Boucicault and William Shakespeare in the family home. He also got a small part in Boucicault’s The Shaughraun in the Mechanics’ Theatre, which stood on what was to be the site of the Abbey Theatre.

As his interest in the Irish nationalist cause grew, O’Casey joined the Gaelic League in 1906 and learned the Irish language. At this time, he Gaelicised his name from John Casey to Seán Ó Cathasaigh. He also learned to play the Uilleann pipes and was a founder and secretary of the St. Laurence O’Toole Pipe Band. He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and became involved in the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, which had been established by Jim Larkin to represent the interests of the unskilled labourers who inhabited the Dublin tenements. He participated in the Dublin Lockout but was blacklisted and could not find steady work for some time.

In March 1914, he became General Secretary of Larkin’s Irish Citizen Army, which would soon be run by James Connolly. On 24 July 1914 he resigned from the ICA, after his proposal to deny dual membership to both the ICA and the Irish Volunteers was rejected.

One of his first satirical ballads, “The Grand Oul’ Dame Britannia”, was published in The Workers’ Republic on 15 January 1916 under his penname An Gall Fada.

“Ah, what is all the fuss about?”, says the grand old dame Britannia,

“Is it us you are trying to live without?”, Says the grand old dame Britannia.

“Shut your ears to the Sinn Féin lies, you know every Gael for England dies,″

“And you’ll have Home Rule ‘neath the clear blue skies.” Says the grand old dame Britannia.

— Seán Ó Cathasaigh, Grand Ould Dame Britannia, 1916.

In 1917, his friend Thomas Ashe died in a hunger strike and it inspired him to write. He wrote two laments: one in verse and a longer one in prose. Ballads authored around this time by O’Casey featured in the two editions of Songs of the Wren, published in 1918; these included “The Man from the Daily Mail”, which, along with “The Grand Oul’ Dame Britannia”, became Irish rebel music staples. A common theme was opposition to Irish conscription into the British Army during the First World War.

He spent the next five years writing plays. In 1918, when both his sister and mother died (in January and September, respectively), the St Laurence O’Toole National Club commissioned him to write the play The Frost in the Flower. He had been in the St Laurence O’Toole Pipe Band and played on the hurling team. The club declined to put the play on out of fear that its satirical treatment of several parishioners would cause resentment. O’Casey then submitted the play to the Abbey Theatre, which also rejected it but encouraged him to continue writing. Eventually, O’Casey expanded the play to three acts and retitled it The Harvest Festival.

O’Casey’s first accepted play, The Shadow of a Gunman, was performed at the Abbey Theatre in 1923. This was the beginning of a relationship that was to be fruitful for both theatre and dramatist but which ended in some bitterness.

The play deals with the impact of revolutionary politics on Dublin’s slums and their inhabitants, and is understood to be set in Mountjoy Square, where he lived during the 1916 Easter Rising. It was followed by Juno and the Paycock (1924) and The Plough and the Stars (1926). The former deals with the effect of the Irish Civil War on the working class poor of the city, while the latter is set in Dublin in 1916 around the Easter Rising. Both plays deal realistically with the rhetoric and dangers of Irish patriotism, with tenement life, self-deception, and survival; they are tragi-comedies in which violent death throws into relief the blustering masculine bravado of characters such as Jack Boyle and Joxer Daly in Juno and the Paycock and the heroic resilience of Juno herself or of Bessie Burgess in The Plough and the Stars. Juno and the Paycock became a film directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

The Plough and the Stars was not well received by the Abbey audience and resulted in scenes reminiscent of the riots that greeted J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World in 1907. There was a riot reported on the fourth night of the show. His depiction of sex and religion even offended some of the actors, who refused to speak their lines. The full-scale riot occurred partly because the play was thought to be an attack on the men in the rising and partly in protest in opposition to the animated appearance of a prostitute in Act 2.

W. B. Yeats got onto the stage and roared at the audience: “You have disgraced yourselves again”. The takings of the play were substantial compared with the previous week. O’Casey gave up his job and became a full-time writer.

After the incident, even though the play was well liked by most of the Abbey goers, Liam O’Flaherty, Austin Clarke and F. R. Higgins launched an attack against it in the press. O’Casey believed it was an attack on Yeats, that they were using O’Casey’s play to berate Yeats.

In 1952 he appeared in a play by Irish playwright Teresa Deevy called “The Wild Goose” in which he played the part of Father Ryan. O’Casey was involved in numerous productions with the Abbey; these can be found in the Abbey Archives. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: Catalogue Irish History Seven – Irish Literature – Poetry – Music – Theatre · Catalogue No.10 – International Literature · Drama · Drama – Rare · Irish History of Theatre · Irish Literature · Irish Literature – 20th Century · Irish Literature – Rare · Irish Plays · Plays · Playwright · Playwrights

- Language: English

- Inventory Number: 31008AB

EUR 375,--

© 2024 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software