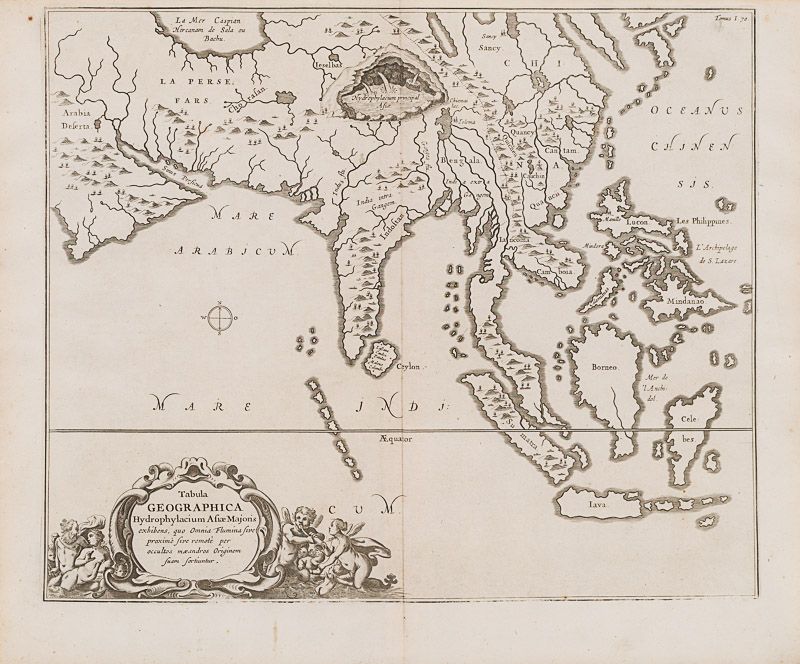

Kircher, Tabula Geographica Hydrophylacium Asiae Majoris Exhibens, quo Omnia Flu

Tabula Geographica Hydrophylacium Asiae Majoris Exhibens, quo Omnia Flumina sive proxime sive remote per occultos maeandros Originem suam Sortiuntur.

Original copper engraving. Amsterdam, Kircher, [c.1665]. Plate Size: 41.2 cm x 34.2 cm. Sheet Size: 37.5 cm x 39.2 cm. Original Map in very good condition. Very minor traces of browning to outer margins.

[Burden 382, ill. pl. 382, p. 487].

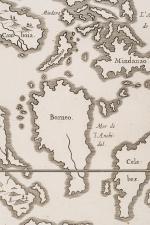

A richly elaborate and highly imaginative map of the Asia, centering upon an emaciated Indian sub-continent, and including the Arabian peninsula, Persia and Caspian Sea in the west across to China, Cambodia and the Malay peninsula in the east. Off the mainland lie the Philippine and Indonesian archipelagos: Luzon, Mindanao, ‘Celebes’ (Sulawesi), Borneo, Java and Sumatra are all identified. Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the unnamed Maldives are shown off the Indian coast. Farther east, along the Chinese coast are a smaller chain of islands – possibly a speculatively shaped but unidentified Formosa/Taiwan or a misplaced Japan. Apart from an apparently crowded Ceylon – containing settlements like Colombo – only three cities are shown on the map – Manilla and the more mysterious ‘Tolema’ and ‘Sancy’. Mountains and rivers, such as the Ganges and the Indus, are depicted pictorially.

In the lower left corner of the map is a highly decorative cartouche featuring putti, a potentially amorous Neptune and more reticent companion, and a mermaid who is fixated upon her horn-blowing companion.

What makes the map – from Kircher’s ‘Mundus Subterraneous’, first issued in 1665 – all the more fascinating is that it was used to illustrate his unique hydro-geological theories about the world’s ocean currents, tides, volcanic distribution, and core structure of the planet. Kircher hypothesized that tides and currents are caused by water moving to and from a massive subterranean ocean. Kircher further postulated that water entered and exited the subterranean ocean via a number of great abysses situated around the globe. In addition, he believed that massive underground lakes lay beneath most of the world’s great mountain ranges – here shown as the massive below-ground ‘Hydrophylacium Principal Asiae’ in what can be assumed are the Himalayas in Nepal and Tibet. These lakes, Kircher argued – as shown here – were the sources of the world’s major rivers. While obviously disproven subsequently, Kircher’s maps were among the first thematic maps to attempt to scientifically illustrate and explain global geological and oceanographic phenomena.

Kircher was also fascinated with China and Chinese culture, language and system of writing. He published an encyclopaedic ‘China Illustrata’ in 1667 in which he sought to link Chinese culture and the West by arguing (albeit unsuccessfully) that the Chinese script originated from Egyptian hieroglyphs. Utilizing evidence of early Christians in China provided by the Nestorian Stele (tablet), Kircher also alluded to the mythical Christian king, Prestor John and his fanciful empire in Tibet or Nepal.

Athanasius Kircher, (1602 – 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works, most notably in the fields of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci for his enormous range of interests, and has been honoured with the title “Master of a Hundred Arts”. A refugee from the war-torn German territories, he taught for more than forty years at the Roman College, where he set up a museum-type cabinet of curiosities or wunderkammer. A resurgence of interest in Kircher has occurred within the scholarly community in recent decades. A scientific star in his day, towards the end of his life he was eclipsed by the rationalism of René Descartes and others. In the late 20th century, however, the aesthetic qualities of his work again began to be appreciated. One modern scholar, Alan Cutler, described Kircher as “a giant among seventeenth-century scholars”, and “one of the last thinkers who could rightfully claim all knowledge as his domain”. Another scholar, Edward W. Schmidt, referred to Kircher as “the last Renaissance man”. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: 17th Century · Arabia · Asia · Asian Map · Cartography · Catalogue No.5 – Maps of the World · China · Hydrology · India · Indonesia · Map · Original Engraving · Original Map · Original Maps · Philippines · Rare Map – China · Rare Map Asia · Rare Map Philippines · Rare Map Southeast Asia · Rivers · Vintage Map

- Inventory Number: 200049AG

EUR 945,--

© 2025 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software