Taylor, The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living.

The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living / The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying [Original 1828 Edition – Two Volumes in One] Volume I: The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living – In which are described the means and instruments of obtaining every virtue, and the remedies against every vice, and considerations serving to the resisting all temptations, together with prayers containing the whole duty of a Christian and the parts of devotion fitted for all occasions, and furnished for all necessities. / Volume II: The rule and exercises of Holy Dying- In which are described the means and instruments of preparing ourselves and others respectively, for a blessed death, and the remedies against the evils and temptations proper to the state of sicknesse : together with prayers and acts of vertue to be used by sick and dying persons, or by others standing in their attendance : to which are added rules for the visitation of the sick and offices proper for that ministery.

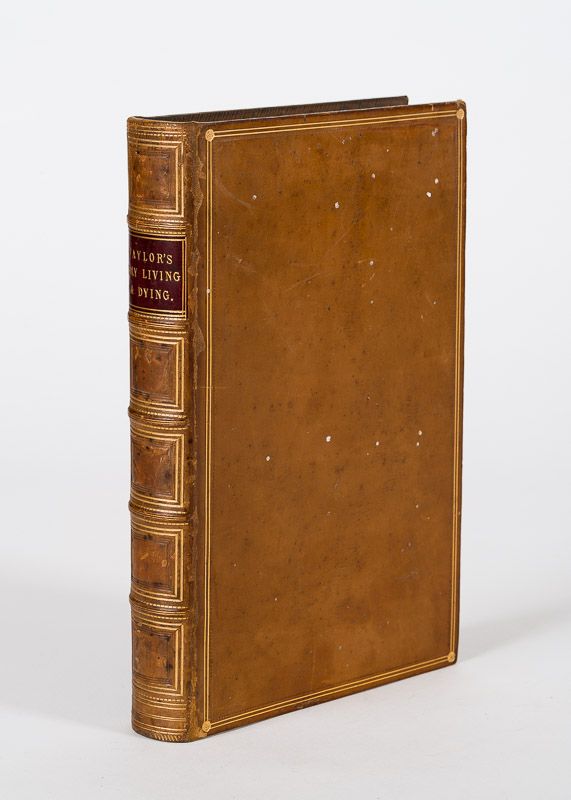

London, Printed for C. and J. Rivington and others, 1828. 24 cm. Volume I: X, 313, (5) pages including Index. / Volume II: XIX, 259, (4) pages including Index. Original Hardcover / Full calf with gilt lettering and ornament to spine. Excellent, firm condition with only very minor signs of external wear. On excellent paper with some occasional foxing. Beautiful, marbled endpapers. From the reference library of Hans Christian Andersen – Translator Erik Haugaard. With his Exlibris to the pastedown.

Includes for example the following chapters: ‘Of Christian Sobriety’; ‘Of Christian Justice’; ‘Of Christian Religion’ etc.

Jeremy Taylor (1613–1667) was a cleric in the Church of England who achieved fame as an author during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. He is sometimes known as the “Shakespeare of Divines” for his poetic style of expression, and he is frequently cited as one of the greatest prose writers in the English language. He is remembered in the Church of England’s calendar of saints with a Lesser Festival on 13 August.

Taylor was under the patronage of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. He went on to become chaplain in ordinary to King Charles I as a result of Laud’s sponsorship. This made him politically suspect when Laud was tried for treason and executed in 1649 by the Puritan parliament during the English Civil War. After the parliamentary victory over the King, he was briefly imprisoned several times.

Eventually, he was allowed to live quietly in Wales, where he became the private chaplain of the Earl of Carbery. At the Restoration, his political star was on the rise, and he was made Bishop of Down and Connor in Ireland. He also became vice-chancellor of the University of Dublin.

Taylor was born in Cambridge, the son of a barber. He was baptised on 15 August 1613. His father was educated and taught him grammar and mathematics. He was then educated at the Perse School, Cambridge, before going to Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge University where he gained a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1630/1631 and a Master of Arts degree in 1634.

The best evidence of his diligence as a student is the enormous learning of which he showed so easy a command in later years. In 1633, although still below the canonical age, he took holy orders, and accepted the invitation of Thomas Risden, a former fellow-student, to supply his place for a short time as lecturer in St Paul’s.

During the next fifteen years Taylor’s movements are not easily traced. He seems to have been in London during the last weeks of Charles I in 1649, from whom he is said to have received his watch and some jewels which had ornamented the ebony case in which he kept his Bible. He had been taken prisoner with other Royalists while besieging Cardigan Castle on 4 February 1645. In 1646 he is found in partnership with two other deprived clergymen, keeping a school at Newton Hall, in the parish of Llanfihangel Aberbythych, Carmarthenshire. Here he became private chaplain to and benefited from the hospitality of Richard Vaughan, 2nd Earl of Carbery, whose mansion, Golden Grove, is immortalised in the title of Taylor’s still popular manual of devotion, and whose first wife was a constant friend of Taylor. Alice, the third Lady Carbery, was the original of the Lady in John Milton’s Comus. Taylor’s first wife had died early in 1651. His second wife was Joanna Bridges or Brydges, said to be a natural daughter of Charles I. She owned a good estate, though probably impoverished by Parliamentarian exactions, at Mandinam, in Carmarthenshire. Several years following their marriage, they moved to Ireland. Two daughters were born to them.

From time to time Taylor appears in London in the company of his friend John Evelyn, in whose Diary and correspondence his name repeatedly occurs. He was imprisoned three times: in 1645 for an injudicious preface to his Golden Grove; again in Chepstow Castle, from May to October 1655, on what charge does not appear; and a third time in the Tower in 1657, because of the indiscretion of his publisher, Richard Royston, who had decorated his Collection of Offices with a print representing Christ in the attitude of prayer.

He probably left Wales in 1657, and his immediate connection with Golden Grove seems to have ceased two years earlier. In 1658, through the kind offices of his friend John Evelyn, Taylor was offered a lectureship in Lisburn, Co. Antrim, by Edward Conway, 2nd Viscount Conway. At first he declined a post in which the duty as to be shared with a Presbyterian, or, as he expressed it, where a Presbyterian and myself shall be like Castor and Pollux, the one up and the other down, and to which also a very meagre salary was attached. He was, however, induced to take it, and found in his patron’s property at Portmore, on Lough Neagh, a congenial retreat.

At the Restoration, instead of being recalled to England, as he probably expected and certainly desired, he was appointed to the see of Down and Connor, to which was shortly added the additional responsibility for overviewing the adjacent diocese of Dromore. As bishop he commissioned in 1661 the building of a new cathedral at Dromore for the Dromore diocese. He was also made a member of the Irish privy council and vice-chancellor of the University of Dublin. None of these positions was a sinecure.

Of the university he wrote:

I found all things in a perfect disorder … a heap of men and boys, but no body of a college, no one member, either fellow or scholar, having any legal title to his place, but thrust in by tyranny or chance.

Accordingly, he set himself vigorously to the task of framing and enforcing regulations for the admission and conduct of members of the university, and also of establishing lectureships. His episcopal labours were still more arduous. There were, at the date of the Restoration, about seventy Presbyterian ministers in the north of Ireland, and most of these were from the west of Scotland, with a dislike for Episcopacy which distinguished the Covenanting party. No wonder that Taylor, writing to the James Butler, 12th Earl of Ormonde shortly after his consecration, should have said, “I perceive myself thrown into a place of torment”. His letters perhaps somewhat exaggerate the danger in which he lived, but there is no doubt that his authority was resisted and his overtures rejected.

This was Taylor’s golden opportunity to show the wise toleration he had earlier advocated, but the new bishop had nothing to offer the Presbyterian clergy but the alternative of submission to episcopal ordination and jurisdiction or deprivation. Consequently, at his first visitation, he declared thirty-six churches to be vacant; and repossession was secured on his orders. At the same time many of the gentry were apparently won over by his undoubted sincerity and devotedness as well as by his eloquence. With the Roman Catholic element of the population he was less successful. Not knowing the English language, and firmly attached to their traditional forms of worship, they were nonetheless compelled to attend a service they considered profane, conducted in a language they could not understand.

As Reginald Heber says

No part of the administration of Ireland by the English crown has been more extraordinary and more unfortunate than the system pursued for the introduction of the Reformed religion. At the instance of the Irish bishops Taylor undertook his last great work, the Dissuasive from Popery (in two parts, 1664 and 1667), but, as he himself seemed partly conscious, he might have more effectually gained his end by adopting the methods of Ussher and William Bedell, and inducing his clergy to acquire the Irish language.

The troubles of his episcopate no doubt shortened his life. Nor were domestic sorrows wanting in these later years. In 1661 he buried, at Lisburn, Edward, the only surviving son of his second marriage. His eldest son, an officer in the army, was killed in a duel; and his second son, Charles, who was destined for the ministry, left Trinity College and became companion and secretary to George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, at whose house he died. The day after his son’s funeral Taylor caught fever from a sick person he had visited, and, after a ten days illness, he died at Lisburn on 13 August 1667. He was buried at Dromore Cathedral where an Apsidal Chancel was later built over the crypt where he was laid to rest. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: Catalogue No.7 – Religion · Catalogue One – History of Law · Erik Haugaard Collection · Religion – Rare

- Language: English

- Inventory Number: 44659AB

EUR 380,--

© 2026 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software