Vivian, Tunisia and the Modern Barbary Pirates.

Tunisia and the Modern Barbary Pirates. Illustrated with Photographs and a Map.

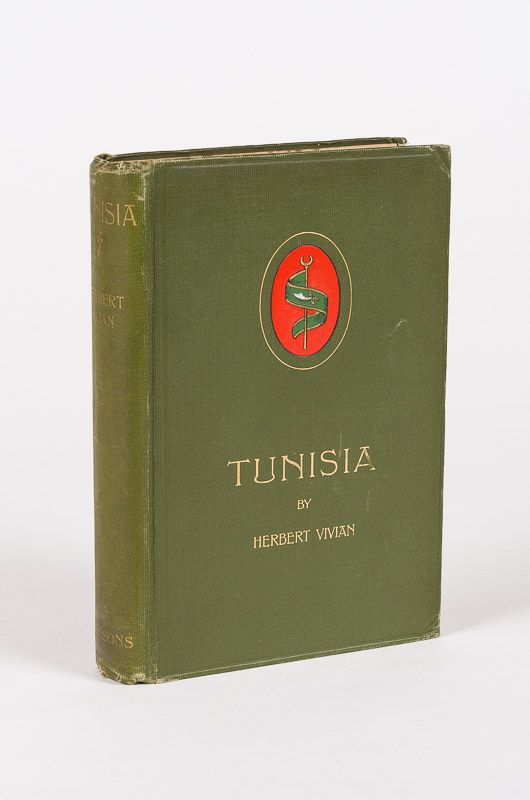

London, C. Arthur Pearson Limited, 1899. 15 cm x 22 cm. Frontispiece, XVI, 341 pages. 72 photographic illustrations. One fold-out map of Tunisian region as frontispiece. Hardcover [publisher’s original green cloth] with gilt lettering on spine and front board. Vignette on front board. Top gilt edge. Very good condition with only minor signs of external wear. Minor wear evident at spine ends. Some foxing to endpapers and pastedowns. Otherwise interior is bright and clean.

Includes for example the following chapters: The Bey / The Modern Barbary Pirates / French Administration / Arabs / Harems / Conversion to Islam / The Jews of Tunis / Negroes / The French Quarter / Carthage / Susa / Susa to Sfax / El Kef / The Mejerda / Vulture-Prines / Sheshias / The Tuaregs / The Court of the Kadi / Sadiki College / Tripoli / etc.

The chapter entitled ‘Jews and Niggers’ is unsettling for modern eyes, with the author making use ready of numerous anti-Semitic tropes. Tunis, Vivian tells us, “is one of the chief resorts of Hebrews on the Mediterranean. They are of mixed race and origin, and many of them are difficult to distinguish in appearance from civilized beings…. Vulture-noses are by no means characteristic.” (p.118) From this seeming nadir the author descends apace. The following pages illustrate the author’s unabashed personal opinions and views, which in turn, highlights how widespread anti-Semitism and its stereotypes and prejudices were engrained in Victorian society. “In our sense of the words, literature and art are practically non-existent among the Jews.” (p.142) This description cut across the Victorian Anglo-Jewish narratives of progress, cultural affinities and assimilation. [Nadia Valman, ‘Semitism and Criticism: Victorian Anglo-Jewish Literary History,’ Victorian Literature and Culture Vol. 27, No. 1 (1999), pp. 235-248]

What is most evident is Vivian’s distrust of Jews. He saw in them an irrevocably foreign element which would seek to the material benefits of the society in which they lived while nevertheless retaining their separate identities. In Tunis, the Jews “greedily seize” the educational opportunities that French occupation offers them, “glibly repeating Christian prayers and hymns and creeds which they do not profess to believe for a moment.” To Vivian’s mind the Jews present a threat – at once irredeemably alien while having the potential to superficially assimilate to further their own interests. “In another generation or two we shall find in Tunis an educated Jewish population, cherishing no sympathies with the French Government or any form of European civilization, and able to beat any commercial rivals out of the field. Their subtle ingenuity will certainly constitute a greater menace to French colonial enterprise than any possibility of an Arab rising” (p.120). They will rise through to dominance through subterfuge: simply, the Jews are not to be trusted. They are deemed guilty of “fraudulent bankruptcies” through which “they become very wealthy” (p.121). In Tunis, “just as much as anywhere else, “the chief occupation of a Jew is the handling of money.” At almost every street corner “you may see the tables of the money-changers covered with piles of copper coin, and in every case conducted by Jews.” Usury, that age-old libel, is standard practice.

Little sympathy is extended to the Jews’ obvious poverty and second-class status within Tunisian society. Vivian paints a pen-picture of the teeming streets of the Jewish quarter to emphasize the difference of the Jews. “When you have passed through the Gate of France at Tunis, you feel that you have crossed the threshold from Europe into Africa.” The Jewish quarter is immediately encountered in this non-European space. “Every ugly smell, from the sickening odours of rags and rotting meat, confronts you. In every shop and corner are black masses of sluggish flies, and, still more revolting, insects feasting upon a wealth of offal. The streets take all sorts of unreasonable curves as the fancy seizes them, and houses project or retire from the roadway in the most hopeless disorder. On either hand are blind alleys and dark cellars, suggestive of hideous mysteries.” (p.128-29). This is not just foreign it is fetid.

Jewish Otherness is again evident at wedding ceremonies and Vivian’s description of a Jewish bride. “It is only in Tunis and among the negroes of Central Africa that a woman’s attractiveness is measured by weight.” (p.140)

Vivian, through his use of language and example, is seeking to emphasise the Jews’ ‘otherness’ from European civilization. From a British point-of-view, this criticism was of great concern coming as it did in a period of mass immigration of European Jewry. In 1850 British Jews numbered only 35,000. However between 1880 and 1906 the Jewish population rose dramatically to 300,000 resulting from waves of Yiddish-speaking, poverty-stricken Russian and Eastern European Jews fleeing Tsarist pogroms, repression, persecution, and economic hardships. The sheer numbers arriving prompted the first Aliens Act (1905), which restricted immigration into the country. Jews were accused of taking jobs from locals, of pushing up rents by accepting overcrowded conditions, and of aggravating the appalling working conditions in many of the local trades. (‘David Philips ‘Community Citizenship and Community Social Quality: the British Jewish Community at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,’ available online from Sheffield University)

This immigration raised age old concerns about Jews and their place in Britain. Vivian’s descriptions of Tunis can be understood as analogous to the fears being aired in the face of this influx of new arrivals in places such as the East End of London – London taking ninety percent of the Jewish immigrants during this period. British voices began to question current laws of citizenship and demanded a tightening or even fundamental change from about terms of citizenship and nationality. Fears concerning the Jews as the eternal alien and internal threats found fertile soil in the imagination of many and not just in Britain – narratives that would have murderous consequences across Europe in the 20th century. Not excusing Vivian’s own personal responsibilities for his anti-Semitism, his prejudices are those of the milleu from which he was writing.

Herbert Vivian (3 April 1865 – 18 April 1940) was a British journalist, writer and newspaper proprietor. He was a leader of the Neo-Jacobite Revival of the 1890s, a movement that was opposed to parliamentary sovereignty and sought to restore the deposed House of Stuart.

In 1890 Vivian was a co-founder and editor of “The Whirlwind,” a weekly literary magazine that published articles by Oscar Wilde.

In the late 1890s he was a travel correspondent for a number of newspapers and wrote books on travel and foreign regions. The most well-known of Vivian’s travel books was “Servia. The Poor Man’s Paradise,” published in 1896.

After the war, he became an extreme monarchist and virulently anti-Bolshevik. In 1920, Vivian met Benito Mussolini and Gabriele D’Annunzio in Italy and became an admirer of fascism, particularly Italian Fascism. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: 19th Century · 19th Century – Rare · Africa – Rare · Africa, North · Africana Collection of Rare Books · Algeria · Algiers · Anti-Semtism · Antisemitism · Barbary States · Colonial History · Colonial History – Rare · French Imperialism · Jewish history · Jewish History – Rare · Jews · Judaica · Maghreb · Map, African · Maps · North Africa · Racism · Racist Author · Travel · Travel Africa – Rare · Tunisia

- Language: English

- Inventory Number: 120029AB

EUR 220,--

© 2025 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software