Le Brocquy, Small Archive of personal correspondence between irish-american writ

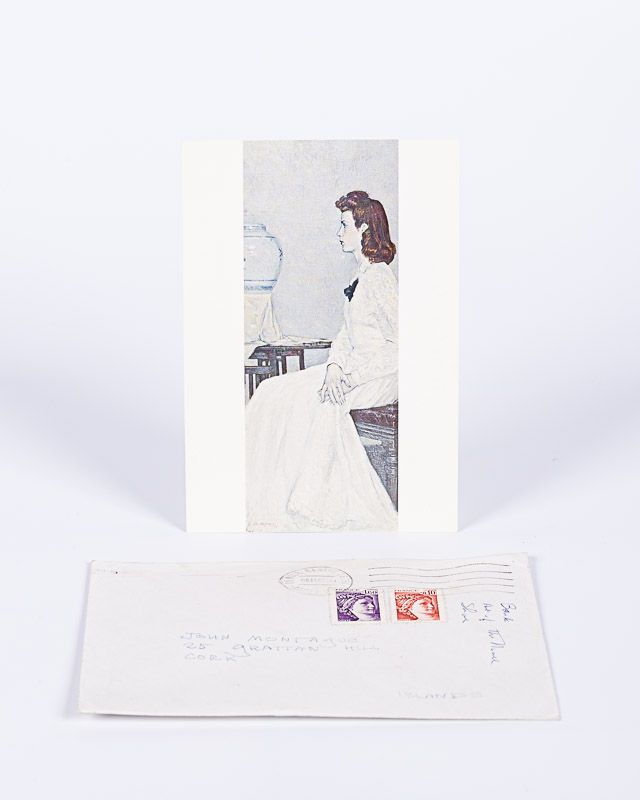

Small Archive of personal correspondence between irish-american writer John Montague and irish artist Louis Le Brocquy plus many related items. The correspondence also includes John Montague touching on Samuel Beckett. The core of the collection includes 1. Extremely insightful and important, very personal manuscript-letter from John Montague to Louis Le Brocquy – Inside an envelope addressed by John Montague to Louis Le Brocquy at his french residence ‘Domaine des Combes’ with Louis Le Brocquy’s answer carefully tucked into the same envelope, treasured by John Montague. The densely filled, very personal 4-page-manuscript letter from John Montague, is dated Christmas 1981, written after “a sabbatical [..] on a long tour which led me as far as Los Angeles” and is a strong reflection of John Montague’s personal struggles, thoughts and influences as a writer; he talks about his ten years of teaching in the US “after O’Riada’s death led to a vacuum” and “enduring the semi-bourgeois limbo of Cork”. Montague speaks about the time “after the harness came off” and he “felt quite strange, and after thirty years my stammer returned in painful, nearly uncontrollable force”. Montague even touches on his fears about his health and continues “I clocked into a clinic for a rest cure….so far liver excellent, so it is not Sean or Brendan all over again (in any case, loving the stuff, as you do, I can’t overdrink; the tastebuds are against it)”. Montague dives into comparisons with Samuel Beckett: “″Did you realize that Sam Beckett was under analysis at the Tavistock Clinic for two years ? – The early Beckett is a smart alec; the break comes when he has to survive in post-war France and accept “his own darkness”. Montague also touches on his struggle with his mother “Isn’t it terrible that we spend up to nearly middle-[a]ge coping with the traumas of youth, with no way round it ? – I have cleared/cleaned/buried & forgiven my mother in my next book “The Dead Kingdom”….” – The letter continues to talk about books, “the Landslide Manuscript”, poetry and his work etc. etc. He mentions a Dupin “play” which “will travel in my Paris luggage”. Montague also touches on the subject of the Irish Troubles and writes “I have always, by the way, believed that 1916 may have been a mistake as Yeats said: “For England may keep faith – For all is said and done” / Montague speaks about “My own area of Tyrone is blessedly free from all but minor incidents” – Amazing document of confidence and trust between two irish landmark personalities. 2. Louis Le Brocquy’s answer to John Montague is dated “New Year’s Day 1981”[which should have been 1982]: A. Very personal manuscript Letter – a direct answer to Montague’s letter from “Christmas 1981” (1 sheet with both pages filled in ink and signed “Louis”) in which Le Brocquy reflects on the tense political situation with Northern Ireland and the overall worldwide tension of a looming war / Le Brocquy writes that he did have a “wild hope that when Charlie took office…that he and Thatcher might between them opted a ‘Rhodesian’ solution in the North” / Le Brocquy also writes about the eagerly awaited publication of “Selected Poems” of John Montague and he also asks John if “you thought of collecting Esteban’s and Dupin’s poems in French with your translations ?” – Le Brocquy offers to help with illustrations etc. – Both letters together in an envelope which suggests that John Montague received his letter to Louis le Brocquy back from the Le Brocquy-estate after Le Brocquy’s death. / Also included: B. A manuscript postcard with Le Brocquy’s “Girl in White” as a postcard-reproduction in which Le Brocquy suggests a project with John Montague and sends greetings to Montague’s wife Evelyn and the kids (in envelope from Carros,France) / C. In his function as chairman of Amnesty International, Le Brocquy sends a callout by Amnesty International to John Montague and kindly asks him to support the cause. He sends the callout to John by adding a few manuscript, personal lines of affection (in envelope from Carros,France).

France / Ireland, Carros / Cork, 1980-1981. A4. 4 pages on two sheets (main Montague-letter), 2 pages on 1 sheet (Le Brocquy – answer), 1 postcard, 1 manuscript-letter from Jacques Dupin to John Montague (25.10.1978) about a translation of “L’Éboulement” (Dupin also speaks about Louis le Brocquy in the letter), several pages of letters (mostly typed and signed) from other figures in irish and international literature and art. Original Envelopes. Very good condition with only minor signs of external wear. Besides some ephemeral materials from personalities in Literature and Art, addressed to John Montague, the small collection includes several vintage photographs of John Montague, taken during his acceptance of a honorary Doctorate of Literature at UCC, Cork, as well as a Legislative Resolution by the State of New York (Senator Daly), recognizing and thanking the distinguished author and poet John Montague with this decree on May 26, 1987. Among the lesser interesting materials is a pamphlet titled “Ireland’s Literary Renaissance – 20th century Portraits” in which portraits by Louis Le Brocquy of John Montague and Thomas Kinsella are included. The pamphlet is accompanied by a letter from James White to John Montague in which he explains this being a publication that was released for an exhibition in Chicago and he apologises for the entries being “necessarily short but hopefully reasonably correct”. Provenance: From the private collection of John Montague’s papers in his recently sold West Cork Home.

[John Montague in his early letter to Le Brocquy: “The early Beckett is a smart alec; the break comes when he has to survive in post-war France and accept “his own darkness”]

John Montague (28 February 1929 – 10 December 2016) was an Irish poet. Born in America, he was raised in Ireland. He published a number of volumes of poetry, two collections of short stories and two volumes of memoir. He was one of the best known Irish contemporary poets. In 1998 he became the first occupant of the Ireland Chair of Poetry (essentially Ireland’s poet laureate). In 2010, he was made a Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur, France’s highest civil award.

John Montague was born in Brooklyn, New York City, New York, on 28 February 1929. His father, James Montague, an Ulster Catholic, from County Tyrone, had gone to America in 1925 to join his brother John. Both were sons of John Montague, who had been a JP, combining his legal duties with being a schoolmaster, farmer, postmaster and director of several firms.

John continued as postmaster but James became involved in the turbulent Irish Republican scene in the years after 1916, particularly complicated in areas like Fermanagh and Tyrone, on the borders of the newly divided island.

Molly (Carney) Montague joined her husband James in America in 1928, with their two elder sons. John was born on Bushwick Avenue at St. Catherine’s Hospital, and spent his earliest years playing with his brothers in the streets of Brooklyn, putting nickels on the trolley lines, playing on a tenement roof, seeing early Mickey Mouse movies.

John Montague studied at University College Dublin in 1946. He found an extraordinary contrast between the Ulster of the war years and post-war Dublin, where the atmosphere was introverted and melancholy. Stirred by the example of other student poets (including Thomas Kinsella) he began to publish his first poems in The Dublin Magazine, Envoy, and The Bell, edited by Peadar O’Donnell. But the atmosphere in Dublin was still constrained and Montague left for Yale on a Fulbright Fellowship in 1953.

John had already met Saul Bellow at the Salzburg Seminar in American Studies and now he worked with Robert Penn Warren as well as auditing the classes of several Yale critics, like Rene Wellek and W. K. Wimsatt. He extended his sense of contemporary American literature, attending Indiana Summer School of Letters where he heard Richard Wilbur, Leslie Fiedler, and John Crowe Ransom, who like the Irish poet Austin Clarke, encouraged Montague, finding him a job at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1954 and 1955.

From Iowa to Berkeley, a year of graduate school convinced Montague that he should return to Ireland. He sailed back to France that summer, to marry his first wife, Madeleine, whom he had met in Iowa, where she was also on a Fulbright; they settled in Herbert Street, Dublin, a few doors down from Brendan Behan. Working by day at the Irish Tourist Office, Montague at last gathered his first book of poems, Poisoned Lands (1961).

That year he also moved to Bray in which he went to St Brendan’s and forgot to hand up his essay to Mr.Meyler, to a small studio a block away from Samuel Beckett, with whom he slowly became on good drinking terms. There, he also met another neighbour, the French poet Claude Esteban, with whom he became friends – Montague recently translated into English and published some of his poems.

A regular rhythm of publication saw his first book of stories, Death of a Chieftain (1964) after which the musical group The Chieftains were named, his second book of poems, A Chosen Light (1967), Tides (1970), the latter both also published by Swallow in the U.S.

All during the 1960s, Montague continued to work on his long poem, The Rough Field, a task that coincided with the outbreak of the Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland. A Patriotic Suite appeared in 1966, Hymn to the New Omagh Road and The Bread God in 1968, and A New Siege, dedicated to Bernadette Devlin which he read outside Armagh Jail in 1970. In 1972, the long poem was finally published by Dolmen/Oxford and Montague returned to Ireland, to live and teach in University College Cork, at the request of his friend, the composer Seán Ó Riada, where he inspired an impressive field of young writers including Gregory O’Donoghue, Sean Dunne, Thomas McCarthy, William Wall, Maurice Riordan, Gerry Murphy, Greg Delanty and Theo Dorgan. In a birthday tribute for his 80th, William Wall wrote: “It would be impossible to overestimate his influence on the young writers who went to UCC (University College Cork) at that time.” The Rough Field (1972) was slowly recognised as a major achievement.

Settled in Cork with his second wife, Evelyn Robson, Montague published an anthology, The Faber Book of Irish Verse (1974) with a book of lyrics, A Slow Dance (1975). Recognition was now beginning to come, with the award of the Irish American Cultural Institute in 1976, the first Marten Toonder Award in 1977, and in 1978, the Alice Hunt Bartlett Award for The Great Cloak, “the best book of poetry in two years” according to the Poetry Society of Great Britain. A Guggenheim in 1979 and 1980 enabled Montague to complete his Selected Poems (1982) and his second long poem, The Dead Kingdom (1984) both co-published by Dolmen (Ireland), Oxford (England), Wake Forest University Press (US) and Exile Editions (Canada).

In 1987, Montague was awarded an honorary doctor of letters by the State University of New York at Buffalo. Governor Mario M. Cuomo presented Montague a citation in 1987 “for his outstanding literary achievements and his contributions to the people of New York.” Montague serves as distinguished writer-in-residence for the New York State Writers Institute during each spring semester, teaching workshops in fiction and poetry and a class in the English Department of the University of Albany.

In 1995, Montague and his second wife, Evelyn, separated, and he formed a partnership with American student Elizabeth Wassell (later to be author of The Honey Plain (1997)). He has 2 daughters with Evelyn, Sibyl and Oonagh. In 1998, Montague was named the first Irish professor of poetry, a three-year appointment to be divided among The Queen’s University in Belfast, Trinity College Dublin, and University College Dublin. He held this title from 1998 to 2001, when he was succeeded by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill. In 2008, he published A Ball of Fire, a collection of all his fiction including the short novella The Lost Notebook. Montague died at the age of 87 in Nice on 10 December 2016 after complications from a recent surgery. He is survived by his wife Elizabeth Wassell, daughters Oonagh and Sibyl and grandchildren Eve and Theo. Montague’s poems chart boyhood, schooldays, love and relationships. Family and personal history and Ireland’s history are also prominent themes in his poetry.

Montague is noted for his vowel harmonies, his use of assonance and echo, and his handling of the line and line break. Montague believes that a poem appears with its own rhythm and that rhythm and line lengths should be based on living speech. (Wikipedia)

_____________________________________

Louis le Brocquy (10 November 1916 – 25 April 2012) was an Irish painter born in Dublin to Albert and Sybil le Brocquy. His work received many accolades in a career that spanned some seventy years of creative practice. In 1956, he represented Ireland at the Venice Biennale, winning the Premio Acquisito Internationale (a once-off award when the event was acquired by the Nestle Corporation) with A Family (National Gallery of Ireland), subsequently included in the historic exhibition Fifty Years of Modern Art Brussels, World Fair 1958. The same year he married the Irish painter Anne Madden and left London to work in the French Midi.

Le Brocquy is widely acclaimed for his evocative “Portrait Heads” of literary figures and fellow artists, which include William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, and his friends Samuel Beckett, Francis Bacon and Seamus Heaney, in recent years le Brocquy’s early “Tinker” subjects and Grey period “Family” paintings, have attracted attention on the international marketplace placing le Brocquy within a very select group of British and Irish artists whose works have commanded prices in excess of £1 million during their lifetimes that include Lucian Freud, David Hockney, Frank Auerbach, and Francis Bacon.

The artist’s work is represented in numerous public collections from the Guggenheim, New York to the Tate Modern, London. In Ireland, he is honoured as the first and only painter to be included during his lifetime in the Permanent Irish Collection of the National Gallery of Ireland. Le Brocquy died on 25 April 2012 and was survived by his daughter Seyre from his first marriage (1938-1948) to Jean Stoney, and his two grandsons John-Paul and David; his second wife Anne Madden, and their two sons, Pierre and Alexis.

le Brocquy designed the covers for the albums Lark in the Morning and The Rising of the Moon. (Wikipedia)

- Keywords: Autograph – Rare · Catalogue Four – International Art · Catalogue Irish History – Art and Architecture · Catalogue No.10 – International Literature · Catalogue Seventeen – Autographs and Manuscripts · Collection Literature Rare · Inscribed · Irish Art – Rare · Irish Literature – Rare · Library & Collection Building · Manuscript / Autograph – Rare · Manuscript Letter · Manuscript Letter Rare · Manuscript Letter Signed · Manuscript Literature Rare · Manuscript Material – Rare · Samuel Beckett · Signed

- Language: English

- Inventory Number: 28869AB

© 2026 Inanna Rare Books Ltd. | Powered by HESCOM-Software